During the late 13th century, Kublai Khan, the leader of the Mongol Empire, launched two invasions against Japan. The first invasion occurred in 1274, while the second invasion, also known as the Battle of Kōan, happened in 1281.

This war was a significant encounter between the Mongol Empire and feudal Japan. Samurai warriors banded together to fight off the foreign Mongol forces, marking one of the few failures of the dominant Mongol Empire.

Key Takeaways

- The Second Mongol Invasion of Japan in 1281 was a pivotal event. Known as the Battle of Kōan, it showcased Japan’s defensive strength against the combined forces under the Mongols.

- Japan prepared for the invasion by building a stone wall at Hakata Bay. They also used small, maneuverable boats for effective coastal defense.

- The Mongol army, led by Kublai Khan, faced a major setback. A surprise typhoon, referred to as the kamikaze, devastated their fleet and forced their retreat.

- The battle’s outcome boosted Japan’s national pride and belief in divine protection. For the Mongols, it resulted in refraining from further invasions due to severe losses.

- The victory led to financial and military strain for Japan’s Hōjō Regency. This strain contributed to their eventual decline, showing the complex consequences of a significant military event.

Prelude of Second Mongol Invasion of Japan

The Second Mongol Invasion of Japan was driven by the Mongol Empire’s desire to expand into Japan, under the leadership of Kublai Khan. After their initial failure at the Battle of Bun’ei in 1274, the Mongols regrouped, capitalizing on their recent conquest of Southern China and the Southern Sung empire.

By 1279, the Mongols had virtually completed their conquest of China and established the Yuan dynasty. Kublai Khan had gained substantial maritime resources and leveraged the surrendered Sung navy for their second invasion of Japan.

Aware of the impending threat, Japan, under the Kamakura Shōgunate, fortified its defenses. The Japanese, well-informed about Mongol activities, anticipated another attack and used the intervening years to build substantial coastal defenses.

A notable example was the construction of a stone wall along Hakata Bay, possibly stretching up to twenty-five miles and standing fifteen feet high. This wall was a significant strategic development with a sloping defensive side for horseback access and a vertical sea-facing side. Despite proposals for an ocean-going fleet to take the fight to the Mongols, financial constraints led to a focus on smaller, more maneuverable coastal ships.

On the Mongol side, Kublai Khan’s consolidation of power in China enabled him to amass an enormous force.

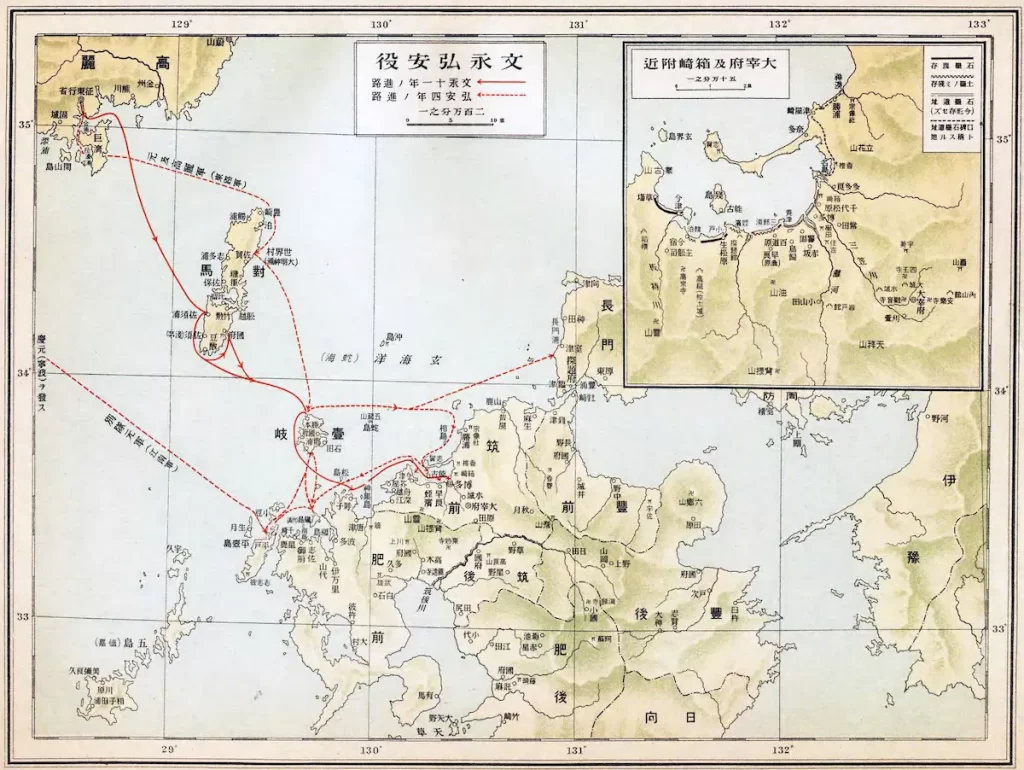

He commanded the construction of warships in the Yangtze area and, in 1281, ordered the formation of a formidable invasion force. This force comprised two divisions:

- the Eastern Route Division from Goryeo (present-day Korea), including 900 ships, 10,000 Korean soldiers, 17,000 Korean sailors, and

- the Chiang-nan (South of the Yangtze) Division from southeast China, boasting an impressive 3,500 ships, 100,000 Chinese soldiers and 60,000 Chinese sailors.

The plan was for these divisions to merge at Iki before launching a concerted attack on Japan.

Japan organized the western provinces of Honshu and Kyūshū for coastal defense, with a system for rapidly mobilizing forces. Efforts were made to ensure compliance with defense summons and to prepare for potential surprise attacks.

With their defenses bolstered by both physical fortifications and strategic planning, Japan braced for the impending conflict. The stage was set for a monumental clash as the Mongols’ vast naval force approached their target.

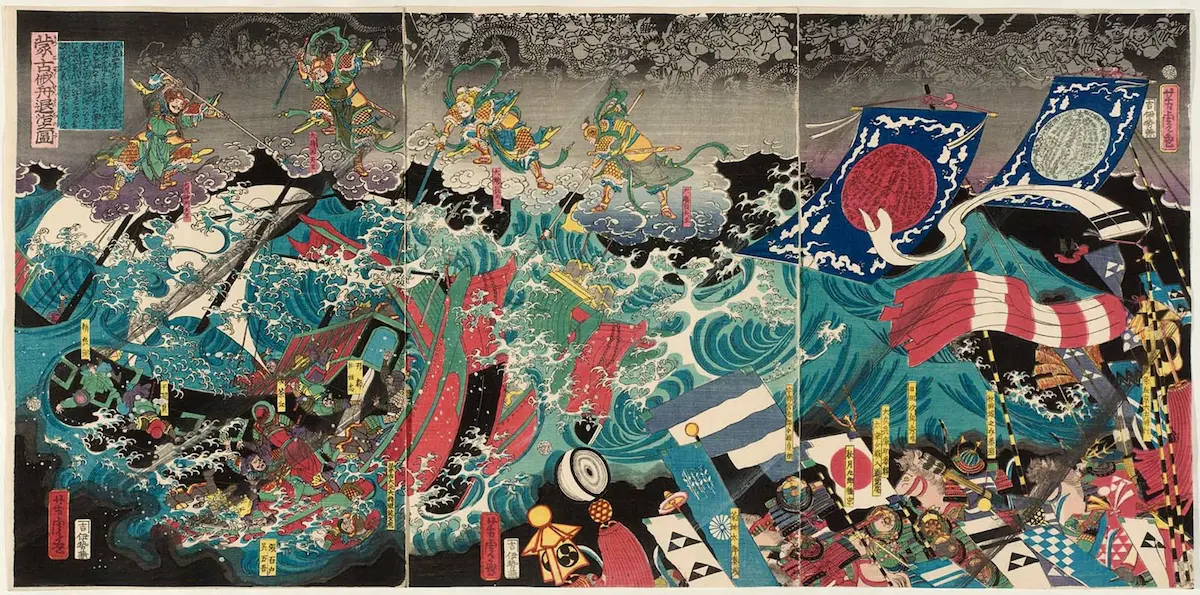

The Battles of the Second Mongol Invasion of Japan

The invasion began in earnest in 1281. The Eastern Route Division, joined by 15,000 Chinese and Mongols, launched an initial assault from Korea. They invaded Tsushima on 9 June, meeting fierce resistance far more intense than in the first invasion. This was followed by an attack on Iki on 14 June. Meanwhile, the Chinese fleet, part of the ‘South of the Yangtze’ force, struggled with manning and provisioning its vast number of ships, delaying its departure.

In a strategic move, the Eastern army advanced ahead of schedule, hoping to outpace their allies. On 21 June, Japanese lookouts spotted the Mongol fleet, which included a diversionary detachment heading towards western Honshu. The main Mongol force attempted to land at Shiga spit at the end of Hakata Bay’s wall. Despite several days of fighting, only a small contingent managed to land, facing stiff resistance from the Japanese.

The Japanese defense was notable for using small, swift boats carrying ten to fifteen men each. These boats enabled the Japanese to execute hit-and-run raids on Mongol ships at night. Samurai warriors displayed extraordinary bravery, often boarding Mongol ships by knocking down their own masts to create bridges.

In one remarkable instance, thirty samurai swam to a Mongol ship, decapitated the crew, and swam back. Another notable incident involved Kusano Jirō, who, despite losing an arm and facing a barrage of arrows, managed to board and set fire to a Mongol ship, capturing twenty-one heads.

The climax of these naval skirmishes was a daring daytime raid led by Kono Michiari. Deceiving the Mongols into thinking they were coming to surrender, Michiari and his men boarded a Mongol ship, killed the captain, set the vessel ablaze, and escaped with a high-ranking officer as captive.

However, the battle’s turning point occurred with the arrival of the Mongol’s ‘South of the Yangtze’ force. On 12 August, this force merged with the Eastern army for a final assault on Japan. The noise from their meeting, filled with drums and cheers, was heard on land, bolstering the Japanese defenders’ resolve.

As the battle peaked, the Japanese, recognizing the enormity of the threat, turned to prayer.

In a remarkable coincidence or divine intervention, as some believed, a violent typhoon, later dubbed ‘kamikaze’ (divine wind), struck on 15 August 1281. This storm devastated the Mongol fleet, causing catastrophic losses and effectively ending the invasion.

The Mongols, now suffering from an epidemic and confined to their cramped ships, were forced into a desperate situation. The delayed arrival of the Yangtze force, combined with the typhoon’s destruction, left the Mongol invasion in shambles.

The storm was seen as a divine intervention by the Japanese, further strengthening their will to defend and leading to the eventual withdrawal of the Mongol forces. This fierce battle and the miraculous storm marked the end of the Second Mongol Invasion of Japan.

Aftermath of the Second Mongol Invasion of Japan

The aftermath of the Second Mongol Invasion, particularly the Battle of Kōan, had profound and lasting impacts on both Japan and the Mongol Empire.

The Mongol’s defeat, primarily due to the devastating kamikaze (divine wind), resulted in massive losses. The Chinese fleet alone lost over half of its 100,000 men, marking one of the most significant defeats in Mongol military history.

Kublai Khan, despite plans for a third invasion, never realized this ambition, as the colossal loss of life and resources in the Battle of Kōan was a significant deterrent.

In Japan, the victory had far-reaching effects. The Japanese viewed the kamikaze as a divine weapon, a symbol of Japan’s protection by the gods.

This belief was so ingrained that it later inspired the naming of the kamikaze pilots of the Second World War, who saw themselves as continuing this legacy of divine defense.

The Battle of Kōan victory significantly bolstered Japanese pride and national identity, reinforcing the notion of divine favor and protection.

The victory was not without its costs, though. The Hōjō Regency, ruling Japan then, faced financial difficulties due to the expenses incurred in rewarding warriors, paying for religious services, and maintaining coastal defenses for the subsequent thirty years. This financial strain contributed to the decline of the Hōjō domination.

The successful defense against the Mongols also led to a shift in military and political dynamics within Japan. The bakufu, the military government, reinforced its authority, implementing measures to collect taxes and expanding its control over military conscription.

The aftermath of the invasion saw a heightened sense of vigilance and preparedness, with continued defense duties and military contributions required from the warriors, particularly in Kyushu.

Moreover, the bakufu’s response to the invasion demonstrated its ability to mobilize and organize large-scale defensive efforts effectively, reflecting a maturation of Japan’s feudal military structure. This organization was evident in its strategic use of the stone walls and the swift deployment of its naval forces.

In the broader context, the Mongol invasions and the resultant Japanese victories played a crucial role in shaping the medieval history of East Asia. The invasions of 1274 and 1281 were among the few failures of the Mongol Empire, a dominant force in Eurasia during the 13th century. They showcased the resilience and military acumen of the Japanese.

The Battle of Kōan, thus, stands not only as a significant military event but also as a defining moment in the formation of Japanese national consciousness and identity.

Frequently Asked Questions

When did the Second Mongol Invasion of Japan take place?

The Second Mongol Invasion of Japan occurred in 1281.

How did the Japanese prepare for the Second Mongol Invasion?

To prepare for the invasion, Japan constructed a lengthy stone wall at Hakata Bay and deployed small, agile boats for coastal defense.

Why did the Mongols fail to invade Japan?

The Mongols failed to conquer Japan primarily due to a devastating typhoon, known as kamikaze, which destroyed much of their fleet.

Further Reading

- The Samurai – A Military History by Stephen Turnbull

- The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 3 (Medieval Japan)