In 939, during the Heian period of Japan, a significant rebellion known as the Tengyō no Ran erupted. It was led by Taira no Masakado, a provincial noble from the Taira Clan. He boldly claimed the title of “New Emperor” and challenged the central government’s authority.

This rebellion was a crucial moment in Japanese history. It questioned the power of the imperial court in Kyōto and set the stage for future changes in the country’s political landscape.

Discover the events leading up to the rebellion, the forces involved, the fierce battle, and the consequences of Masakado’s audacious uprising.

Key Takeaways

- The Tengyō no Ran was a rebellion led by Taira no Masakado in 939. It challenged the authority of the imperial court in Japan during the Heian period.

- The anti-Masakado alliance led by Taira Sadamori and Fujiwara Hidesato ultimately overwhelmed Taira no Masakado’s fragmented troops.

- The aftermath of the rebellion set a precedent for the increasing power of regional warrior leaders. This marked a shift away from central authority and towards feudalism.

- Taira no Masakado became a legendary figure, symbolizing resistance against central authority. His story foreshadowed the rise of the samurai class in Japan.

Prelude to Rebellion of Taira no Masakado

The Tengyō no Ran, a significant uprising in Japan’s history, was rooted in the political and social landscape of the early 10th century. This period was marked by a shift in power dynamics, with local warlords gaining influence at the expense of the central government.

In 935, the seeds of rebellion were sown in the Kantō region, the area around present-day Tokyo, by Taira no Masakado, a member of the powerful Taira family. Taira no Masakado was also a descendant of Emperor Kanmu, the 50th emperor of Japan.

Initially starting as an internal family feud, Masakado’s conflict rapidly escalated into a broader revolt against the central authority.

His grievances were partly driven by the resistance of local landowners to the heavy taxation imposed by provincial authorities. These authorities were predominantly Masakado’s relatives.

Masakado’s audacious actions, such as expelling Heian-appointed governors from several provinces and declaring himself the new emperor (shinnō) of the Kantō plain in 939, posed a direct challenge to the imperial court.

This bold move was preceded by his capture of government headquarters in Hitachi and seven other provinces, demonstrating his growing military prowess and territorial control.

The central government, initially dismissive of Masakado’s uprising due to a history of banditry and minor revolts in the eastern provinces, eventually realized the gravity of the situation. The revolt’s expansion and Masakado’s self-proclamation as emperor significantly threatened the Heian court’s authority and ability to govern.

This prelude set the stage for a major conflict, as the court grappled with the need to suppress Masakado’s rebellion and reassert its dominance over the Kanto region.

The stage was thus set for a dramatic confrontation that would significantly impact the political landscape of Japan.

Forces and Strategies

The forces involved in the Tengyō no Ran were distinct in composition and strategy, reflecting the era’s shifting military practices.

Taira Masakado’s army comprised his close followers (Jusha), a permanent bodyguard or army of mounted warriors, allies (banrui), and provincial troops recruited from local cultivators.

These forces were significant in size, at one point numbering up to six thousand men. However, this number fluctuated greatly throughout the conflict.

Masakado’s strategy hinged on utilizing his mounted warriors, skilled in archery, and the mass tactics of peasant foot soldiers armed with spears and shields. This approach mirrored the traditional tactics of the earlier imperial conscript armies.

Additionally, both Masakado and his opponents employed scorched earth tactics, burning down houses and destroying stored grain to weaken the resolve of their rivals.

On the other side, the anti-Masakado forces constituted an alliance of warrior leaders from various clans, including Taira, Minamoto, and Fujiwara.

This alliance was characterized by a more decentralized structure, with each leader commanding their group of followers. These groups were known as tō (associations), primarily warriors of equal standing with common interests.

The court’s response to Masakado’s rebellion was multifaceted.

Besides military action, it included prayers and the appointment of Pursuit and Apprehension Agents (tsuibushi) in the eastern provinces. The court also dispatched Fujiwara no Tadafumi, a court commander, to the east.

However, the decisive factor in quelling the rebellion was the third prong of the court’s strategy: reliance on provincial warrior leaders.

This approach was exemplified by the roles of Taira no Sadamori, Masakado’s cousin, and Fujiwara no Hidesato, the Shimotsuke Suppression and Control Agent (ōryōshi), who played pivotal roles in confronting Masakado.

The organizational weaknesses in Masakado’s forces, particularly the lack of a solid retainership system, meant that his coalition force of anti-government landholders tended to fragment, leaving him vulnerable at critical moments.

In contrast, the court’s reliance on local warrior leaders, who had stronger ties and influence in their respective provinces, effectively rallied sufficient forces to counter the rebellion.

The Battles of Rebellion of Taira no Masakado

The culmination of the Tengyō no Ran was a series of battles, marked by intense conflict and strategic maneuvering.

The decisive confrontation occurred in 940 in Shimosa. Here, Masakado’s forces clashed with the government-sanctioned troops led by Taira no Sadamori and Fujiwara no Hidesato.

Masakado, having consolidated his power in the Kanto region and self-proclaimed as the new emperor, found himself facing a formidable coalition.

The anti-Masakado alliance, despite its diverse composition, was united in its objective to suppress the rebellion. This alliance, bolstered by the support and legitimacy provided by the imperial court, posed a severe threat to Masakado’s aspirations.

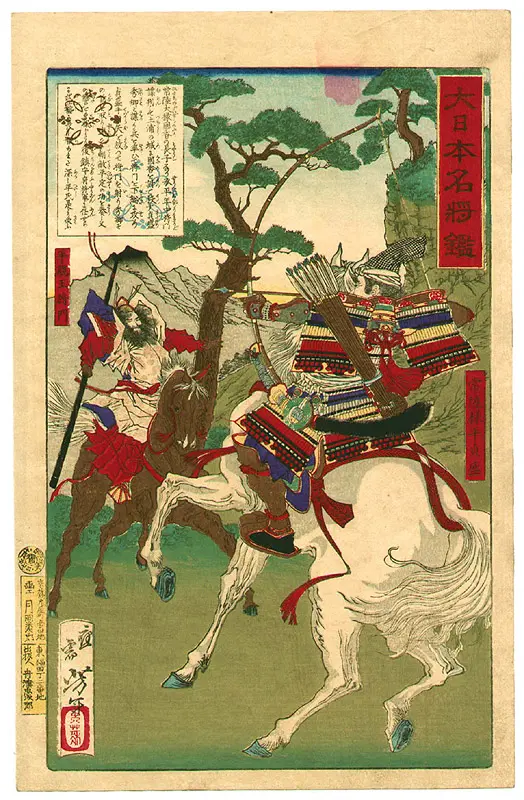

The battle was characterized by traditional Japanese warfare tactics of the period. Masakado’s forces, comprising mounted archers and peasant foot soldiers, engaged in fierce combat with the opposing forces. The tactics of both sides involved archery from horseback and infantry engagements.

Masakado’s strategy relied heavily on the mobility and combat skills of his mounted archers, while the peasant infantry provided bulk and support.

However, Masakado’s forces faced significant challenges.

Their numbers had dwindled due to earlier conflicts and the defection of allies. The lack of a centralized command structure in Masakado’s army also played a role in its eventual downfall.

In contrast, the anti-Masakado forces, though diverse, were better coordinated and had the advantage of support from the central government.

The turning point in the battle came with a strategic move by Hidesato and Sadamori. Utilizing their superior numbers and coordinated tactics, they outflanked and overwhelmed Masakado’s forces.

According to historical accounts, Masakado met his end in this battle, struck down by an arrow. His death effectively marked the end of the rebellion, as without their leader, Masakado’s forces were unable to continue the fight.

His head was famously brought to Kyōto as a warning to others who might challenge the central authority.

The battle was not just a military confrontation but also symbolized the struggle for control between the central authority and the emerging power of regional warlords.

Aftermath of Taira no Masakado’s Rebellion

The aftermath of the Tengyō no Ran had profound implications for Japan’s political and social landscape. The defeat and death of Taira Masakado in 940 marked the end of the most significant challenge to imperial authority at that time.

However, how the rebellion was quelled set a precedent for future interactions between the central government and regional military leaders. Following the suppression of the rebellion, the imperial court sought to reassert its authority in the Kanto region.

The success in quelling the uprising was primarily attributed to the intervention of provincial warrior leaders like Taira Sadamori and Fujiwara Hidesato. This reliance on local military leaders signified a shift in the balance of power.

While the court maintained its nominal authority, the real power increasingly resided with these regional warlords.

The court’s response to the revolt, particularly the granting of titles and rewards to local leaders who assisted in suppressing the rebellion, further legitimized and strengthened the position of these regional military figures.

This policy inadvertently laid the groundwork for the rise of powerful warrior clans, and the gradual decentralization of power away from the imperial court. A trend that would continue in the following centuries.

The rebellion and its suppression also highlighted the limitations of the court’s military capabilities. The reliance on local forces to deal with significant uprisings underscored the declining efficacy of the court’s direct military intervention.

This shift marked the beginning of a transition from a system where military force was centrally controlled to one that was increasingly in the hands of provincial warrior leaders.

The Tengyō no Ran also had cultural and ideological repercussions. The figure of Taira no Masakado became legendary, and he was said to be the first samurai.

He’s often portrayed in later literature and folklore as a symbol of resistance against central authority. This narrative underscored the growing discontent among local leaders with the Heian court’s policies and governance.

In a broader historical context, the aftermath of the Tengyō no Ran can be seen as a precursor to the eventual emergence of feudalism and the rise of samurai in Japan.

The increasing power of local military leaders and the decline of central authority set the stage for the later conflicts and the establishment of the shogunate.

Frequently Asked Questions

What title did Taira no masakado claim for himself?

Taira no Masakado claimed the title of “New Emperor” (shinnō) for himself.

Why did Taira no Masakado rebel against the central government?

Taira no Masakado rebelled against the central government due to grievances over heavy taxation and exactions imposed by provincial authorities, along with a desire to assert local control and challenge the central authority’s dominance.

How was Taira no Masakado killed?

Taira no Masakado was killed in battle, struck by an arrow.

What is the significance of the Tengyō no Ran in Japanese history?

The significance of the Tengyō no Ran in Japanese history lies in its highlighting the shift in power from the central imperial authority to regional warlords, marking a key step towards the feudalization of Japan and setting a precedent for future military governance.