The Jōkyū Disturbance, also known as the Jōkyū War, was a 13th-century conflict in Japan between Retired Emperor Go-Toba and the Hōjō clan of the Kamakura Shogunate. It began with Go-Toba’s attempt to overthrow the shogunate, leading to a series of battles, notably at Uji, resulting in the shogunate’s victory and the capture of Kyoto.

The aftermath saw Go-Toba exiled, the redistribution of lands to shogunate loyalists, and the establishment of the Rokuhara Tandai, significantly reducing the imperial court’s power and marking a shift towards the dominance of military rule in Japan.

Key Takeaways

- The Jōkyū War highlighted the Hōjō clan’s dominance. The Hōjō had reduced the Minamoto clan’s influence and gained control over the Kamakura Shogunate.

- The battle at Uji was crucial. The shogunate’s military superiority and tactics led to Emperor Go-Toba’s defeat.

- Post-war, Go-Toba and key imperial figures were exiled. This marked a major power shift from the imperial court to the warrior class.

- The Rokuhara Tandai was established in Kyoto. It signified the shogunate’s direct control over the imperial court and its consolidated power.

Prelude

Rise of the Hōjō clan

The story begins with Minamoto no Yoritomo, who established the Kamakura Shogunate in the late 12th century. His sudden death in 1199 left a power vacuum. His son, Yoriie, ascended as the Shogun but lacked his father’s political savvy.

The Hōjō clan, related to Yoritomo through marriage, capitalized on this weakness. By the early 13th century, they had established a regency, effectively reducing the Shogun to a figurehead.

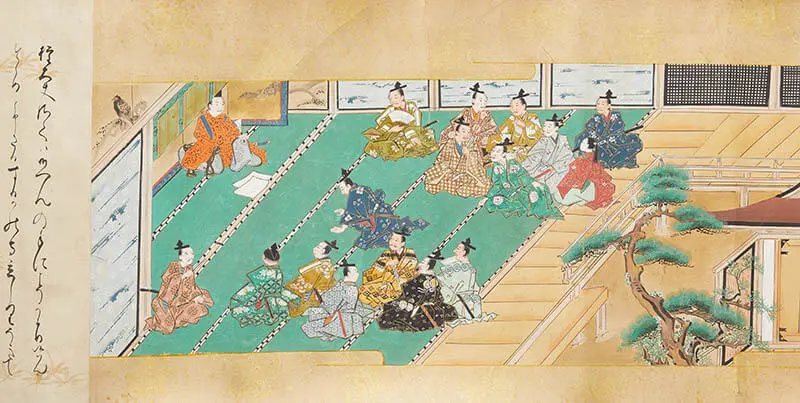

Political Maneuvering of Retired Emperor Go-Toba

Amidst this, Retired Emperor Go-Toba, a keen observer and participant in the political landscape, sought to restore imperial power. He began to build his influence by granting titles and lands to various warriors, including those not aligned with the Kamakura Shogunate.

This move was strategic, aiming to create a power base independent of the shogunate.

Conflict within the Minamoto Clan

The internal struggles within the Minamoto clan, particularly following Yoritomo’s death, created an unstable political environment. Yoriie’s lack of control and subsequent removal, followed by his brother, Sanetomo’s assassination in 1219, further weakened the clan’s grip on power.

The Hōjō’s ascendancy during this period was marked by their strategic marriages and political maneuvering.

Tensions Between Kamakura and the Imperial Court

As the Hōjō regency strengthened, tensions with the imperial court in Kyoto escalated. The imperial court, under the cloistered rule of Retired Emperor Go-Toba, was increasingly dissatisfied with the military government’s dominance.

Go-Toba’s refusal to allow a royal prince to become Shogun, as suggested by regent Hōjō Yoshitoki, was a direct challenge to the shogunate’s authority.

The Brewing Storm

In the lead-up to the Jōkyū War, Retired Emperor Go-Toba capitalized on the discontentment among warriors, providing an alternative source of support and resources.

His recruitment of both gokenin (shogunate vassals) and non-gokenin for his private guard units was a clear sign of his intentions to challenge the Shogunate.

The appointment of a shogun-designate without the shogunate’s consultation and the court’s open defiance marked a significant escalation in the imperial court’s bid for power.

The Final Spark

The final spark occurred in 1221, the third year of the Jōkyū era.

Go-Toba made decisive moves, including the controversial succession decisions and inviting eastern warriors to a festival in Kyoto, effectively revealing their loyalties. Then, several days later, the Imperial Court declared Hōjō Yoshitoki, the regent and representative of the shogunate, to be an outlaw.

The Hōjō clan viewed these actions as a direct threat, setting the stage for a full-scale conflict.

The Battles

Initial Stages and Mobilization

In 1221, upon receiving Retired Emperor Go-Toba’s declaration of war, the Kamakura Shogunate, led by the Hōjō clan, responded swiftly.

The shogunate’s military response was formidable. According to the Azuma Kagami (a historical chronicle), they amassed a counterforce of approximately 190,000 men within a week, a testament to their organizational strength and warrior loyalty. This force was primarily composed of eastern warriors, reflecting the shogunate’s regional power base.

Strategic Advancement to Kyoto

The shogunate forces, under the command of Hōjō Yoshitoki and his son Hōjō Yasutoki, advanced towards Kyoto with a three-pronged strategy. This approach mirrored tactics used in previous conflicts, demonstrating the Hōjō’s military acumen.

The troops moved through different routes – from the mountains, from the north, and via the Tōkaidō road – to converge on Kyoto. As they advanced, they gained additional support from local vassals, further bolstering their strength.

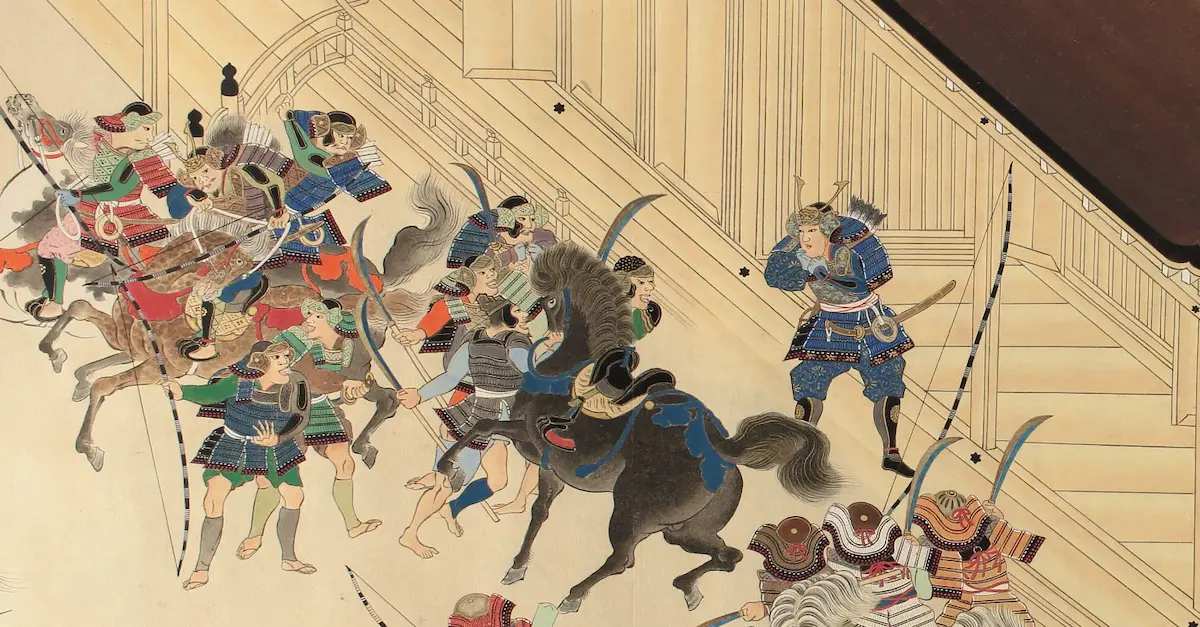

The Battle at Uji

The most critical battle occurred at Uji, a site with historical significance due to previous battles fought there.

The imperial forces, led by Retired Emperor Go-Toba, were significantly outnumbered and less organized. They consisted mainly of warriors from central and western provinces and some eastern defectors. However, they lacked internal coherence and the strong leadership necessary to stand against the disciplined and larger shogunate forces.

The battle at Uji was intense and decisive. Hōjō Yasutoki’s cavalry was crucial in breaking through the imperial defenses.

The imperial army, unable to withstand the shogunate’s onslaught, faced a crushing defeat. This battle effectively marked the war’s turning point, signaling the imperial forces’ imminent fall.

Capture of Kyoto

Following their victory at Uji, the shogunate forces continued their advance and soon entered Kyoto, the heart of imperial power.

The rapid progression of the shogunate’s army left little time for the imperial court to react effectively. The fall of Kyoto to the shogunate’s forces was a significant moment, symbolizing the shift in power dynamics from the imperial court to the military government.

Aftermath

The aftermath of the Jōkyū War was a period of significant restructuring and consolidation of power by the Kamakura Shogunate, particularly the Hōjō clan, which dramatically reshaped Japan’s political and social landscape.

Exile and Punishment

Following the shogunate’s victory, Retired Emperor Go-Toba and key members of the imperial faction faced severe repercussions.

Go-Toba was exiled to the Oki Islands, a remote location from where he never returned. His sons, including Retired Emperors Tsuchimikado and Juntoku, faced similar fates, being banished to Tosa and Sado respectively. Emperor Chūkyō, Juntoku’s son, was deposed and replaced by Emperor Go-Horikawa, a nephew of Go-Toba.

This punishment of the emperor and his allies was unprecedented in Japanese history.

Redistribution of Lands

The shogunate seized this opportunity to redistribute land and power. Approximately 3,000 nobles and warriors who had supported the imperial cause had their lands confiscated. These territories were turned into direct domains of the shogunate.

The victorious vassals were rewarded with new stewardships, known as “Newly Compensated Stewards.” This massive redistribution significantly altered the feudal landscape of Japan, shifting the balance of power towards the warrior class.

Establishment of the Rokuhara Tandai

In a strategic move to strengthen its grip over the imperial court and western Japan, the shogunate established the Rokuhara Tandai in Kyoto. This office, led by Hōjō Tokifusa and Hōjō Yasutoki, was tasked with overseeing the imperial family, commanding the vassals of western Japan, and handling administrative and judicial affairs.

This move effectively placed Kyoto under direct shogunate control, diminishing the imperial court’s autonomy.

Shift in Power Dynamics

The Jōkyū War marked a significant shift in power dynamics from the imperial court to the warrior class. The emperor’s role became largely ceremonial, with real political power concentrated in the hands of the shogunate.

The court lost the power to maintain an army, and decisions regarding imperial succession and court politics were heavily influenced by the shogunate.

Subsequent Reforms and Consolidation

In the years following the Jōkyū War, the Kamakura Shogunate under Hōjō Yasutoki undertook various reforms. These included the establishment of the “Council of State” and the promulgation of the Goseibai Shikimoku, legal codes for the warrior class.

These reforms aimed to stabilize governance and assert the shogunate’s authority across Japan.

Long-term Implications

The Jōkyū War had long-term implications for Japanese society. It reinforced the rise of the warrior class and established the dual system of government, with the shogunate holding real power while the emperor retained a symbolic role.

This period set the stage for the continued dominance of military governments in Japan’s history.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the Jōkyū Disturbance about?

The Jōkyū Disturbance was a conflict in Japan. It involved Retired Emperor Go-Toba and the Hōjō clan of the Kamakura Shogunate.

What were the causes of the Jōkyū Disturbance?

The disturbance was caused by Emperor Go-Toba’s ambitions to regain power. It was also fueled by the weakening of the Minamoto clan and the rise of the Hōjō clan.

What was the outcome of the Jōkyū Disturbance?

The Hōjō clan emerged victorious. This victory led to the exile of Go-Toba and a consolidation of shogunate power.

What was the impact of the Jōkyū Disturbance on Japanese history?

The disturbance had a significant impact on Japanese history. It increased the power of the warrior class and established military rule as the dominant governing force.

Further Readings

- The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 3 (Medieval Japan)

- Japan: A Country Study by Library of Congress