The Heiji Rebellion (Heiji no ran) in Japan’s Heian period was a power struggle between the Taira and Minamoto clans. It was intensified by the political maneuvering of court figures like Fujiwara no Michinori (Shinzei) and Fujiwara no Nobuyori. The conflict reached its zenith with the Minamoto clan’s attack on Sanjō Palace, capturing Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Emperor Nijō.

However, Taira no Kiyomori’s strategic return from pilgrimage and the subsequent escape of the emperors to his side turned the tide against the Minamoto.

The rebellion ended with a decisive defeat of the Minamoto clan, leading to the rise of the Taira clan’s dominance in the Japanese political arena.

Key Takeaways

- The Heiji Rebellion was marked by intense power struggles. It primarily involved the Taira and Minamoto clans within the Imperial court’s political setting.

- A crucial moment was the Minamoto clan’s siege of Sanjō Palace, where they captured Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Emperor Nijō.

- The return of Taira no Kiyomori from a pilgrimage marked a significant turnaround, leading to the defeat of the Minamoto forces.

- The rebellion significantly weakened the Minamoto clan. They lost their leader, Minamoto no Yoshitomo, and many key figures.

- The Heiji Rebellion set the stage for more conflicts, like the Genpei War. It was a key event in shifting power from aristocrats to samurais in Japan.

Prelude to Heiji Rebellion

The Heiji Rebellion unfolded in a period where the traditional courtly rule and the emerging samurai class intersected. This rebellion was preceded by the Hōgen Rebellion of 1156, which marked the beginning of samurai dominance in politics.

The rebellion’s roots can be traced back to the intricate dynamics of the Imperial court. Emperor Go-Shirakawa, practicing cloistered rule, retained significant power after his formal abdication in 1158 in favor of his son, Emperor Nijō. This period saw heightened tensions between various court factions and the samurai class.

A key figure in this context was Fujiwara no Michinori, also known as Shinzei, a scholar and monk with substantial political influence. He was instrumental in implementing Emperor Go-Shirakawa’s policies, particularly regarding estate management. His power, however, engendered resentment among rivals, notably Fujiwara no Nobuyori.

As the Taira clan, led by Taira no Kiyomori, gained prominence, their influence in court affairs grew significantly. Kiyomori, recognized for his role in the Hōgen Rebellion, became a central figure in Kyoto’s political sphere, aligning closely with the cloistered Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Shinzei.

Concurrently, the Minamoto clan, under Minamoto no Yoshitomo, grappled with their diminishing influence. Despite Yoshitomo’s contributions in the Hōgen Rebellion, he found himself eclipsed by the rising Taira clan, fostering a sense of injustice and rivalry.

The stage was set for a major confrontation as these tensions simmered. Nobuyori, aligning with the Minamoto clan, particularly with Yoshitomo, began to plot against Shinzei and the cloistered government.

This alliance between Nobuyori and the Minamoto clan set the foundation for the Heiji Rebellion, with the ambitions and grievances of rival clans converging in Kyoto, the heart of Japan’s political power.

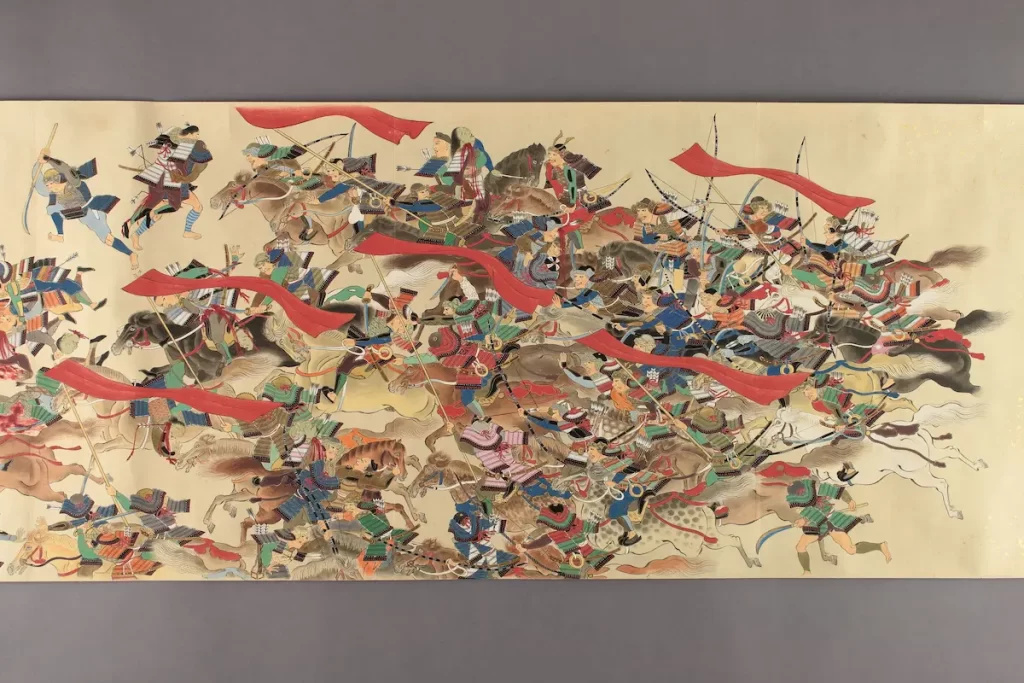

The Battles of Heiji Rebellion

Night Attack on Sanjō Palace

The rebellion’s most iconic episode was the night attack on Sanjō Palace.

In late 1159, seizing the opportunity of Taira no Kiyomori’s absence on a pilgrimage, Fujiwara no Nobuyori and Minamoto no Yoshitomo initiated a daring coup. They targeted the imperial palace, a symbol of authority and the residence of key political figures, including Emperor Go-Shirakawa and Emperor Nijō.

The siege was marked by dramatic and violent scenes. Nobuyori and Yoshitomo’s forces besieged the palace, capturing both emperors and setting the palace ablaze.

This bold move represented a direct challenge to the established order, aiming to shift the balance of power in their favor.

Kiyomori’s Strategic Maneuvering

Kiyomori, aware of the volatile situation in Kyoto during his pilgrimage, made calculated moves upon his return.

Recognizing the potential for deception, he extended peace proposals to Fujiwara no Nobuyori. These approaches, however, were a ruse designed to buy time and give Nobuyori a false sense of security.

Kiyomori’s real intention was to undermine the rebel forces from within and regain control.

Escape of Emperor Nijō and Go-Shirakawa

The turning point in the rebellion was the dramatic escape of Emperor Nijō and the former emperor Go-Shirakawa. With the help of loyalists within Kyoto, they managed to flee the rebels’ clutches, moving first to Kiyomori’s stronghold in Rokuhara.

This escape not only deprived Nobuyori and Yoshitomo of their most valuable hostages but also significantly boosted the morale of the Taira forces and their allies.

Minamoto’s Attempted Retreat and Taira’s Countermove

Realizing the gravity of the situation after the escape of the emperors, the Minamoto forces, led by Minamoto no Yoshitomo, decided to retreat.

However, their exit strategy was thwarted by Kiyomori’s foresight. He had anticipated their move and strategically placed a detachment of Taira forces to block their escape route.

Battle at Rokuhara

The battle at Rokuhara was marked by chaos and desperation. The Minamoto forces found themselves trapped, facing a well-prepared and strategically positioned Taira army.

The Taira forces, leveraging their numerical advantage and strategic positioning, inflicted significant casualties on the Minamoto troops.

The battle was not just a physical confrontation, but also a psychological blow to the Minamoto clan. The disorderly retreat underscored the disarray and demoralization within their ranks.

The Minamoto warriors, renowned for their bravery and skill, were overwhelmed by the superior tactics and coordination of the Taira forces.

Aftermath of Heiji Rebellion

The aftermath of the Heiji Rebellion had far-reaching consequences, reshaping Japan’s political landscape and setting the stage for the eventual Genpei War.

Decimation of the Minamoto Clan and Rise of the Taira

The defeat of the Minamoto clan was a pivotal outcome of the rebellion.

Minamoto no Yoshitomo, the clan’s leader, met a tragic end, betrayed and killed in Owari Province during his escape from Kyoto. This event significantly weakened the Minamoto clan’s military and political power.

Yoshitomo’s sons, Minamoto no Tomonaga and Minamoto no Yoshihira, also became casualties of the conflict.

However, his other sons were spared, including the young Minamoto no Yoritomo, who would later emerge as a critical figure. Yoritomo’s survival was a crucial factor in the clan’s future resurgence.

In contrast, under the leadership of Taira no Kiyomori, the Taira clan emerged significantly strengthened. Kiyomori’s decisive victory and strategic acumen during the rebellion solidified his position as the preeminent military leader in Kyoto.

The Taira clan’s influence expanded, leading to their control over key positions within the government and the court.

Political Repercussions and Cloistered Rule

The Heiji Rebellion also impacted the dynamics of cloistered rule under Emperor Go-Shirakawa. The rebellion’s outcome limited the influence of the cloistered emperor and altered the balance of power in favor of the Taira clan.

Kiyomori, having established himself as a dominant force, began to exert significant influence over court affairs, overshadowing the cloistered emperor’s authority.

The consolidation of power by the Taira clan led to the increased involvement of samurai in government, a departure from the traditional aristocratic rule.

This shift heralded a new era in Japanese politics, where military prowess began to play a more central role in determining political power.

Legacy and Cultural Impact

The Heiji Rebellion’s legacy extended beyond the immediate political changes. It was immortalized in the “Tale of Heiji,” a narrative depicting the rebellion’s events.

This tale, along with others like the “Tale of Hōgen” and the “Tale of Heike,” became part of Japan’s rich literary and cultural heritage, offering insights into the period’s historical and societal contexts.

Moreover, exacerbated by the rebellion, the rivalry between the Taira and Minamoto clans set the stage for the Genpei War.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Heiji Rebellion about?

The Heiji Rebellion was a short but significant conflict in Japan. It involved a power struggle between the Taira and Minamoto clans and key Imperial court figures (Shinzei and Nobuyori).

What was the cause of the Heiji Rebellion?

The rebellion was caused by a thirst for power. Rival clans (Taira and Minamoto) and court officials (Shinzei and Nobuyori) competed for dominance during Emperor Go-Shirakawa’s rule.

How did Emperor Nijo and Emperor escape from their house arrest?

Emperors Nijo and Go-Shirakawa escaped with help from allies. This was during a critical move by Taira no Kiyomori against the rebels.

What was the significance of the Heiji Rebellion in Japanese history?

The crushing of the rebellion led to the Taira clan’s meteoric rise and the samurai’s growing political influence.

Further Readings

- The Cambridge History of Japan: Volume 2 (Heian Japan)

- The Samurai: A Military History by Stephen Turnbull