The rule of the Tokugawa shogunate marked the Edo Period from 1603 to 1868.

It was a time of peace, cultural prosperity, and social order, characterized by the strict Japanese caste system and the seclusion policy of sakoku.

However, it was also the era that witnessed the decline of the samurai class and set the stage for Japan’s emergence into the modern world.

This period concluded with the Meiji Restoration, which led to the end of feudal Japan and the beginning of a new, industrialized nation.

In this article, we will explore the intricacies of the Edo Period, from its societal norms and cultural achievements to the political shifts that led to the dawn of a new age in Japanese history.

Key Takeaways

- The Edo or Tokugawa Period was a time of internal peace and cultural growth in Japan. It lasted from 1603 until 1868.

- Tokugawa Ieyasu established the Tokugawa shogunate, which ruled from Edo, now known as Tokyo. Their rule was characterized by a rigid social hierarchy and isolationist policies.

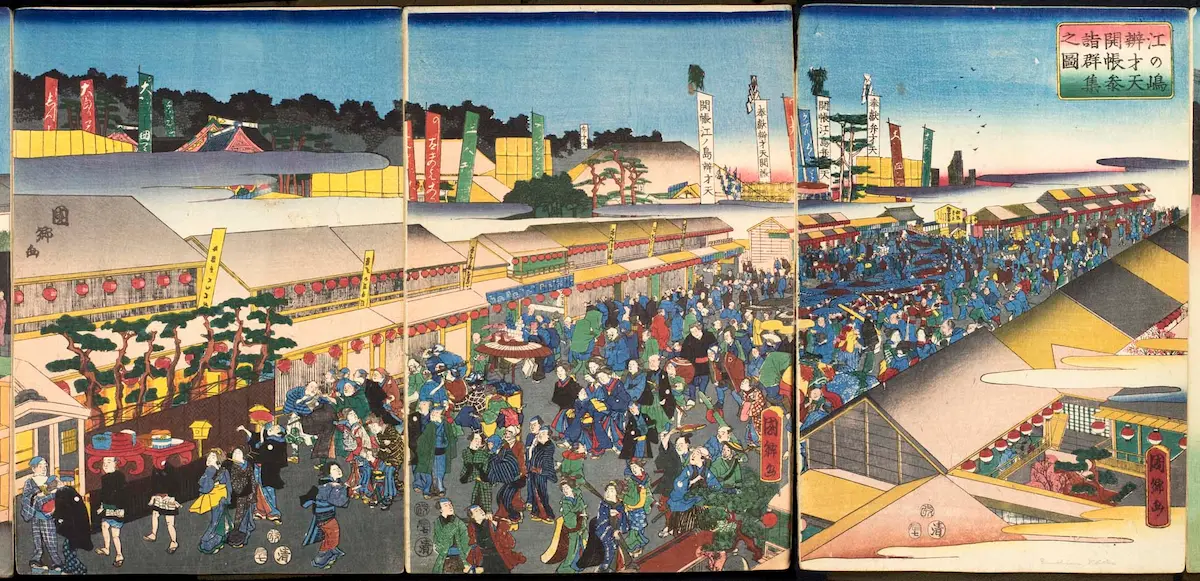

- Arts such as kabuki and ukiyo-e flourished, while the samurai transitioned from warriors to bureaucrats. This shift led to the rise of masterless samurai, or rōnin.

- Commodore Perry’s arrival in 1853 initiated the end of Japan’s isolation. This event led to the Bakumatsu period and ultimately to the Boshin War.

- The Meiji Restoration in 1868 dismantled the Tokugawa shogunate. It marked the end of the samurai era and the beginning of modern Japan.

Brief Overview of the Edo Period (1603–1868)

The Edo period began when Tokugawa Ieyasu established himself as the shogun and set up the Tokugawa shogunate. After a long civil war, the Tokugawa clan succeeded in unifying the country.

This government would rule Japan from the city of Edo, modern-day Tokyo. They ushered in an era of strict social order, economic growth, and a policy of national isolation known as sakoku.

Edo Period Society and Culture

Society during the Edo period was highly structured. The Japanese caste system was rigid, with a clear hierarchy from the samurai at the top to the merchants at the bottom.

Despite their low rank, merchants flourished economically, giving rise to a vibrant urban culture. Arts such as kabuki theater, ukiyo-e, and haiku poetry thrived. Cultural intellects like Hayashi Razan contributed to the development of Confucianism and national studies.

Samurai, adhering to the bushido code, possessed rights such as kiri-sute gomen, which permitted them to punish anyone from a lower class for showing disrespect.

Peace under Tokugawa

The Tokugawa shogunate maintained peace through strict rules and policies.

The shogun controlled the daimyo, regional lords, by imposing a system that required them to spend alternating years in Edo. This system drained their resources and made it difficult for them to rebel.

Isolation from the rest of the world, sakoku, was another key policy. It aimed to prevent foreign influence and maintain the shogunate’s power.

The Tokugawa era was mostly free from war. The samurai, who were once warriors, became bureaucrats or took on other non-military roles.

Key Clashes and Conflicts

Despite the peace, there were still clashes and conflicts. The most significant were those that involved the rōnin, masterless samurai. With no war to fight, many samurai were left without a purpose or a paycheck. Some rōnin became troublemakers or mercenaries, which caused social unrest.

The Shimabara Rebellion in the 1630s was a significant conflict, fueled by religious persecution of Christians. It was a major test of the shogunate’s authority, which they eventually quelled with great force.

Transition to the Meiji Period

The end of Edo period began in the late 1850s when Commodore Perry arrived from the United States. His “black ships” forced Japan to open its ports, ending over two centuries of isolation. This event sparked a chain of changes known as the Bakumatsu.

The dissatisfaction with the shogunate’s handling of foreign pressures led to the Boshin War, a civil conflict between Tokugawa loyalists and those seeking to restore imperial rule.

The war ended with the Tokugawa’s defeat and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration. The samurai class was abolished, and their privileges were stripped away.

Japan transformed from a feudal society to a modern industrialized nation in the Meiji Era. Tokyo, once Edo, became the capital and the center of Japan’s rapid modernization.

The Edo period’s legacy, however, remains a defining chapter in Japan’s rich tapestry of history.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the Edo period?

The Edo period in Japan, lasting from 1603 to 1868, was characterized by the stable rule of the Tokugawa shogunate. This era was marked by peace, cultural growth, and economic development. During this time, a strict social hierarchy was maintained, and Japan pursued isolationist policies.

What was the role of the samurai during the Edo period?

During the Edo period, samurai roles evolved from warriors to administrators. They focused on governance and maintaining societal order, while upholding the ethical code of bushido.

What was the sakoku policy and how did it impact Japan?

Sakoku was Japan’s policy of enforced isolation, initiated in the 17th century. This policy limited foreign trade and influence, fostering cultural uniqueness and economic self-reliance. But, it also led to technological stagnation.

What was the significance of the arrival of Commodore Perry?

Commodore Perry’s arrival in 1853 led to the opening of Japan to foreign trade and influence.

How did the Edo period end?

The Edo period ended with the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Japan underwent major modernization with the return of imperial rule.